Property investing rarely fails because of one mistake. It unravels when the reality of tenants, repairs and constant decisions collides with the idea of “passive” income.

Most investors don’t walk into their rental thinking it will be easy. But many do carry a quiet assumption that once the paperwork is signed, the property will start behaving a bit like a share portfolio: income arrives, costs are predictable, and effort tapers off.

What catches investors off guard isn’t one dramatic mistake. It’s the slow realisation that the mental model they started with doesn’t match the operating reality.

Across hundreds of firsthand accounts, the surprise sounds almost identical:

“I didn’t realise this would feel like a job.”

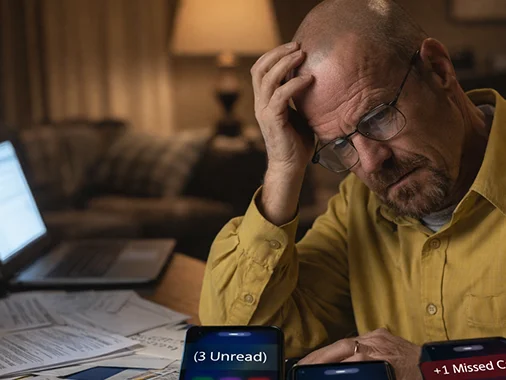

The most repeated regret among property investors has nothing to do with the purchase price. It’s emotional load.

Buyers describe the first six to eighteen months as a period of constant low-grade stress: emails from tenants, coordinating trades, worrying about damage, negotiating boundaries, and lying awake doing mental maths after a repair invoice arrives.

What they underestimated wasn’t intelligence or effort. It was attention.

Rental property demands attention in irregular bursts. Problems don’t arrive neatly. They show up during work meetings, holidays, weekends, and moments when you least feel like making decisions. Even investors who ultimately do well financially say they weren’t prepared for how much headspace the property would occupy early on.

That’s why so many posts start with a variation of the same sentence:

“Being a landlord is not passive income.”

Financial regret usually doesn’t come from buying the “wrong” property. It comes from the gap between the simple forecast in the buyer’s head and the layered reality that emerges after settlement.

Many investors initially model cash flow as rent minus mortgage minus property management fees. Then reality begins adding lines: maintenance, vacancies, leasing fees, insurance shifts, rate changes, and the simple fact that systems fail earlier than expected.

Several investors describe the shock of discovering that a property can technically deliver “cash flow” and still feel like it’s draining money. Repairs arrive in clusters. Appliances fail within months. A single issue can wipe out a year of expected returns.

The regret is rarely about being naive. It’s about not being conservative enough when optimism still felt justified.

Almost every regret thread contains a turning point: the first big repair bill.

Sometimes it’s plumbing. Sometimes HVAC. Sometimes a roof issue that “looked fine” during inspection. Buyers don’t regret inspecting. They regret assuming the inspection covered the most expensive failure modes.

In hindsight, many say they wish they’d thought in terms of systems rather than defects. It’s not about whether something is broken today, but how close it is to failing - and how painful that failure would be if it happened in year one.

That’s also where reserves suddenly feel less theoretical. Investors who didn’t pre-commit to buffers describe the stress of funding repairs reactively, often at the exact moment confidence is already shaky.

Another consistent shock is financing.

Investors often assume the lending experience will feel similar to buying a home. It rarely does. Investment loans introduce different rules, different reserve expectations, and lender-specific overlays, many of which may not be obvious until late in the process.

Buyers describe learning, sometimes days before settlement, that they need more cash than planned - not because the deal changed, but because investment underwriting plays by different norms. Closing costs stack up. Appraisals come in tight. Reserves are suddenly required.

What hurts most isn’t the money. It’s the feeling of being unprepared for a system you didn’t realise had extra rules.

Tenant issues feature heavily in regret stories, but not always in the way outsiders expect.

The most painful posts aren’t about obvious horror stories. They’re about boundary drift. Late rent that’s excused once, then again. Lease clauses that seemed unnecessary at the time. Verbal agreements that felt human, then turned into disputes.

Many landlords describe a moment where they realised kindness trains behaviour - and reversing that later is far harder than setting boundaries early.

This is also where emotional strain shows up most. Evictions, even when justified, are rarely described as purely mechanical. Investors talk about guilt, anxiety, and moral conflict they hadn’t anticipated when the decision felt purely financial.

Legal and compliance issues rarely scare investors upfront. They arrive later, usually attached to a problem.

First-time investors repeatedly say they didn’t realise how jurisdiction-specific renting is until something went wrong. Rent increases, notice periods, eviction procedures, and inspection rules matter far more than expected.

Lease detail regret is especially common. Things that feel “obvious” - parking behaviour, maintenance responsibilities, use of outdoor space — aren’t enforceable if they aren’t written. The phrase “I wish I’d put that in the lease” appears with surprising frequency.

Many buyers attempt to outsource complexity through home warranties, turnkey providers, or remote management platforms. The disappointment isn’t universal, but it’s common enough to form a pattern.

The recurring lesson is not “never outsource.” It’s verify before trusting. Buyers regret assuming third-party numbers were conservative, inspections were exhaustive, or management would act as an owner proxy by default.

Investors who buy remotely often describe how small discrepancies grow without local oversight, turning what looked like convenience into prolonged frustration.

Perhaps the most under-discussed theme is emotional endurance.

Owning a rental changes how people experience money, conflict, and responsibility. Several investors describe feeling trapped - not financially, but psychologically - by a property they can’t emotionally disengage from.

The irony is that many of these investors do fine over time. Appreciation materialises. Rents rise. Systems stabilise. But they wish they’d known how heavy the early phase would feel, so they could decide with clearer eyes.

When investors, and especially first time investors, look back, their regrets don’t turn into clever tactics. They turn into mindset shifts.

They wish they’d treated the purchase as the start of an operating business, not the end of a transaction. They wish they’d assumed costs would arrive earlier than planned.

Most of all, they wish they’d priced their own time, stress, and attention into the decision.

They wish they’d understood that good outcomes don’t come from optimism - they come from margin.

Investment buyers rarely regret buying property altogether. They regret buying it with the wrong mental model.

Rental property isn’t just an asset. It’s a system with people inside it. It demands attention before it delivers returns.

The investors who look back with the least regret aren’t the ones who found the perfect deal. They’re the ones who built enough structure to survive the early reality without losing confidence in the long-term plan.

That’s the part nobody warns you about - and the part that matters most.

It all starts with a confidential conversation.